Running Basics

Metabolism

What is running? It’s the transformation of potential chemical energy from food into kinetic energy of movement (and heat).

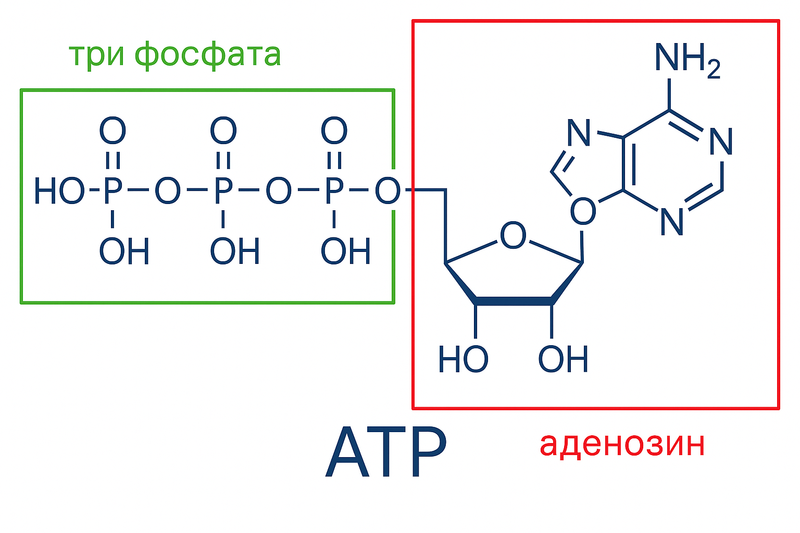

For our muscles to contract, we need adenosine triphosphate (ATP) — our energy currency.

From this adenosine triphosphate, we break off one phosphate group, releasing energy for contraction, and get adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and free phosphate. From adenosine diphosphate, we can also break off another phosphate and get more energy, phosphate, and adenosine monophosphate, but this is a rarer process. If our cell doesn’t have ATP, it can no longer do work. Therefore, when we break down ATP, we need to quickly restore it — reattach the phosphate back.

Right now, we already have some amount of ATP in our cells, so when we start moving, we’ll first break down these ready-made ATPs. This will last us a couple of seconds.

All our energy systems that we’ll examine further are busy reattaching phosphates back to ADP.

Creatine Phosphate

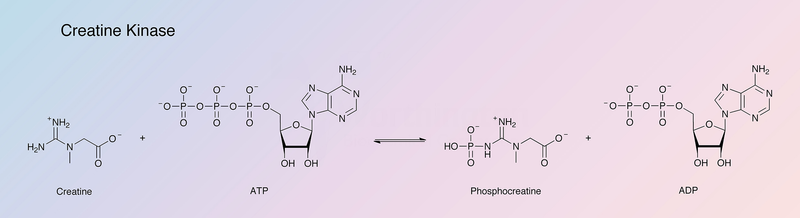

First, creatine kinase or phosphocreatine kinase kicks in — an enzyme thanks to which we can get ATP from creatine phosphate.

Creatine kinase or phosphocreatine kinase

We take creatine phosphate (CrP), break off the phosphate from it, attach it to ADP, and get creatine and adenosine triphosphate. This process is bidirectional, meaning it can go in reverse (to restore CrP content in the cell).

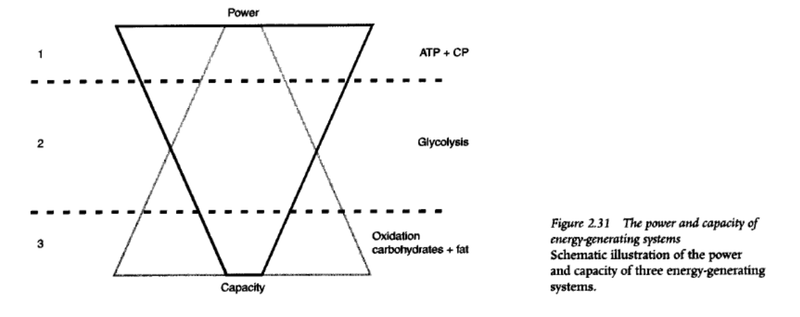

Actually, all our systems turn on simultaneously: both the creatine phosphate system, and glycolysis, and lipolysis, and aerobic processes in the mitochondria. But they all finish their work at different times. So, creatine kinase is one chemical reaction producing 1 ATP, while fast glycolysis is about 10 reactions producing 2 ATP. Therefore, while we’re waiting for glycolysis to bring us its ATPs, we use creatine phosphate as a buffer energy source. We also use it, for example, if we need to suddenly speed up during our marathon to overtake someone. Creatine phosphate will last for 8–10 seconds. Then we’ll need to restore it again.

Glycolysis

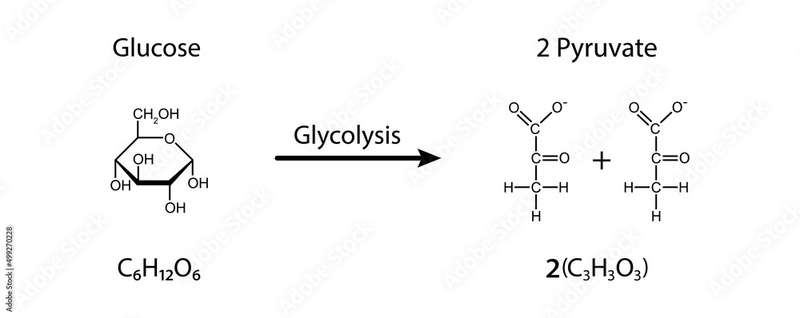

The next ATPs will come from the first part of glycolysis, the so-called anaerobic glycolysis, or glycolytic, or „fast” glycolysis.

The essence of glucose metabolism is this: We take a carbon chain, break it into pieces, getting a little bit of ATP, send the pieces to the mitochondria, add oxygen there, and get a whole bunch more ATP.

Here’s the first part of the process — anaerobic glycolysis. We run on this from a few seconds to a minute. While waiting for ATPs from the next, aerobic part.

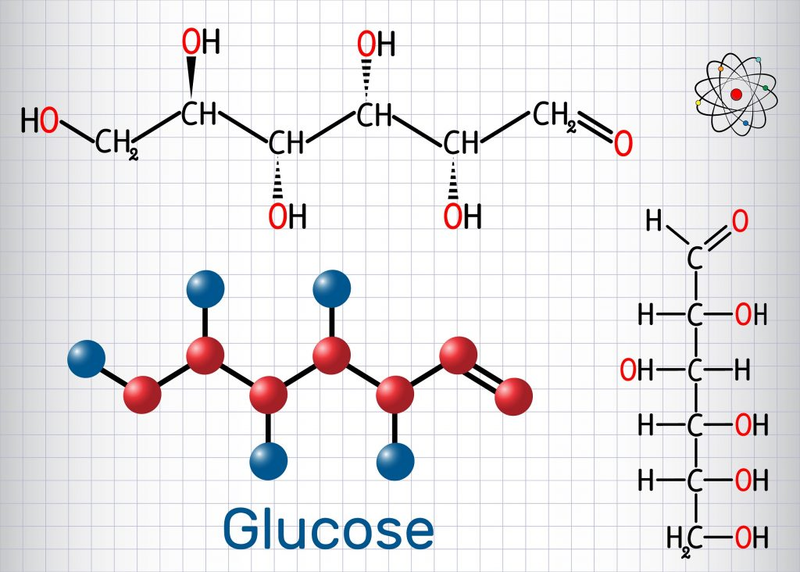

Here, for example, we take one such beautiful glucose molecule.

Glucose is a chain of six carbons, we break it in half and get two pyruvates (pyruvic acid), each with three carbons plus two ATPs as a bonus (net yield):

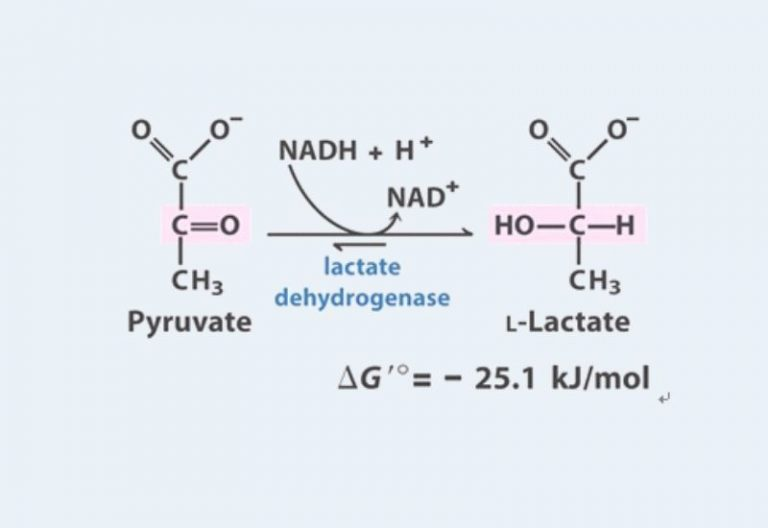

Or pyruvate and lactate. In the picture where glucose was turning into pyruvate, you can notice if you count all the letters that several hydrogens (H) disappeared somewhere. Lactate is the same pyruvate, but plus two more hydrogens:

Pyruvate can proceed right into the mitochondria to produce a bunch more ATP (about 15 from one pyruvate), and lactate can exit the cell and go either into a neighboring cell, into a cell of a neighboring muscle, and also go into the mitochondria to follow the same path as pyruvate, or into the blood, to the brain, to the heart (the brain and heart feed well on lactate), or to the liver, the liver will collect several lactates and convert them back into glucose, then send the glucose back into the blood and to the muscles.

Let’s sum up: we broke glucose in half, getting a little bit of energy, added oxygen to the halves, sent them to the mitochondria, broke them down further there and got a bunch more energy. Actually — this is all one process, but ancient physiology researchers decided to call the first stage an anaerobic process (because oxygen isn’t required to break down glucose into pyruvate, although it’s present in the cell and used in subsequent stages), and the second stage — aerobic (because oxygen is necessary for it).

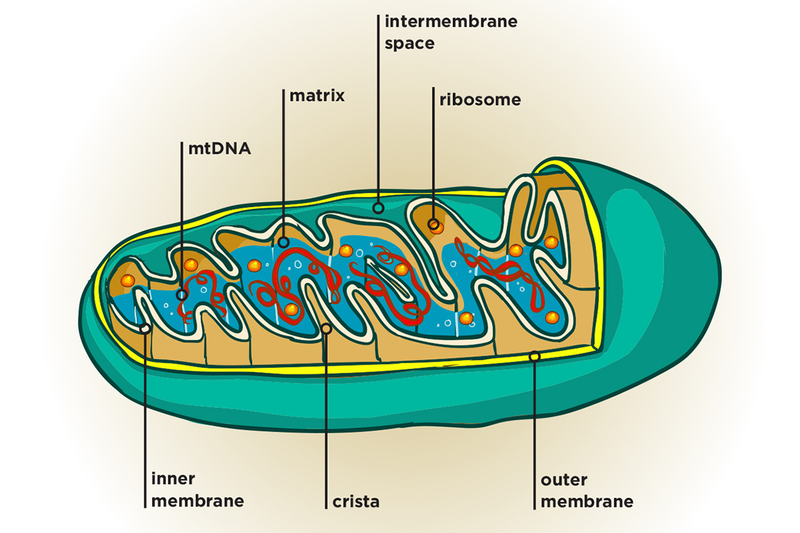

The process of ATP formation in mitochondria is also called cellular respiration. And the mitochondria itself is called the „powerhouse of the cell,” as it’s the main source of energy for the cell.

The main source, but a very slow one. „A hundred thousand million” reactions have to happen there. But the essence of these reactions is this: took food scraps (pyruvate from glucose or fatty acids from triglycerides), added oxygen, got carbon dioxide and water as output, resynthesizing a bunch of ATP in the process.

Lipolysis

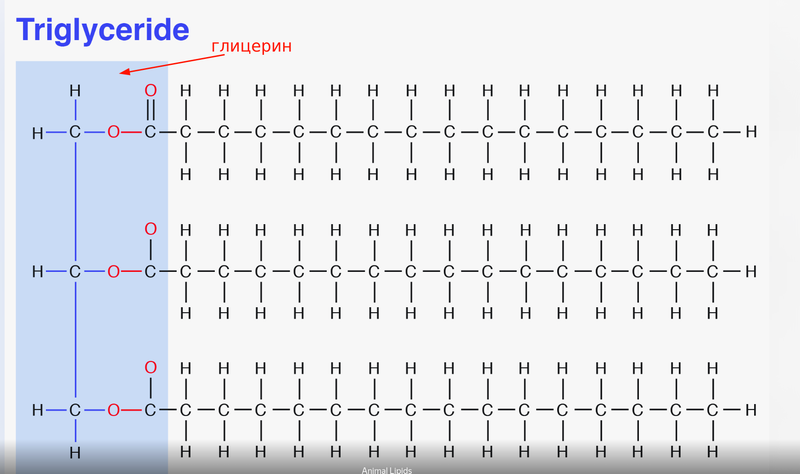

Lipolysis is similar to glycolysis. We take a triglyceride (fat), which consists of glycerol and three fatty acids attached to it.

We break off the fatty acids from glycerol. Look how many carbon chains there are :) Here are 16 carbon bonds drawn for each fatty acid. From one such fatty acid (palmitic acid, C16), we’ll get a whopping 106 ATP molecules in the mitochondria.

There are two problems — first, this is no longer „a hundred thousand million” reactions, but „five hundred thousand million” reactions, and second, these triglycerides still need to be delivered to the cell from the places where we store fat (far away).

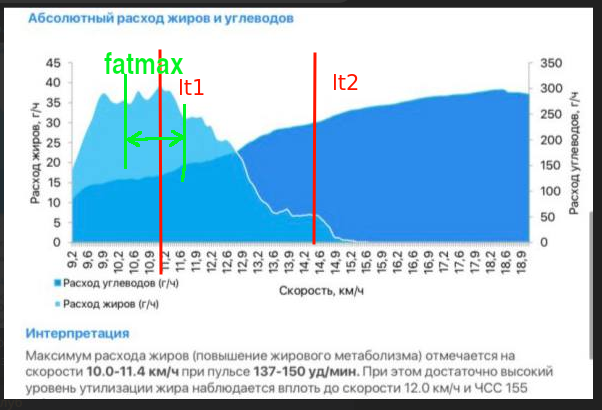

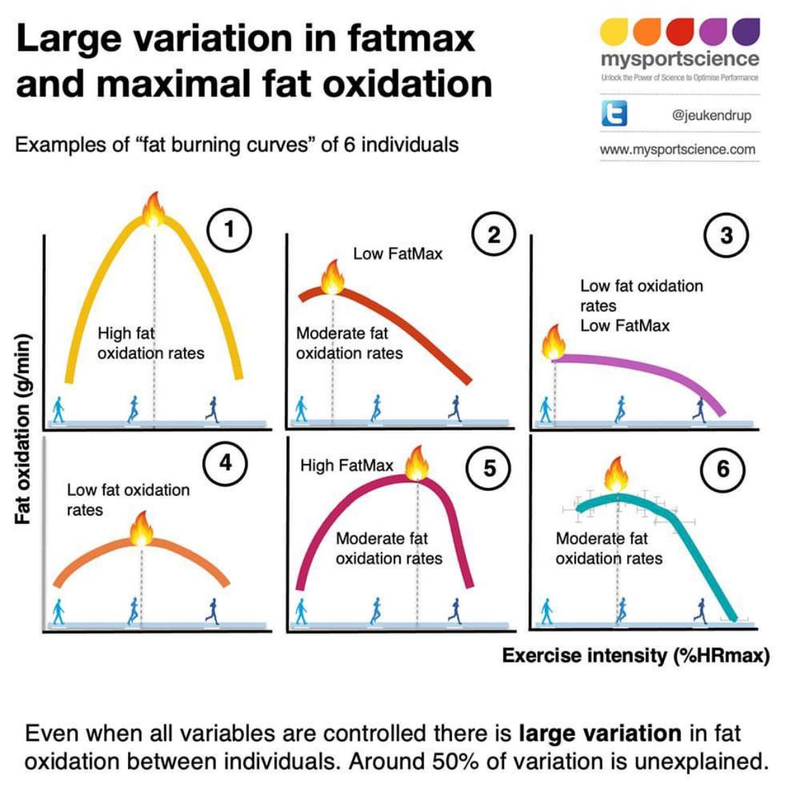

Here’s what the expenditure of fats and carbohydrates looks like for some person. I drew the thresholds and zones myself roughly based on my understanding.

But the fat metabolism curve looks different for different people. Depending on their fitness level and other factors.

Stores and Speed

Glucose is stored in the form of glycogen. About 300–500 grams in muscles and 80–100 in the liver. Total about 400–600 grams, which gives approximately 1600–2400 kcal. This will last us for a competition lasting approximately one and a half to two hours of intense running.

80% of all energy in the human body is stored in the form of fat, in the form of these triglycerides. Approximately 70,000–75,000 kcal. You can consider this reserve inexhaustible.

Let’s summarize:

- We get energy fastest from creatine phosphate, but there’s very little of it — 8-10 seconds and it’s gone.

- Slightly slower, but we get more energy from fast glycolysis — 30 seconds to 2 minutes and it’s gone.

- Even slower, but even more from aerobic glycolysis — until glycogen stores are depleted (90-120 minutes at marathon pace).

- And very slowly, but a lot from fat oxidation.

I imagine it like this: we’re sitting in front of the TV and must constantly eat something. We simultaneously:

- pull out our food stash from our pocket (creatine phosphate) and start eating,

- send the wife to the kitchen for food,

- send grandpa to the garage for lard and pickles.

The wife pulls out a bag of chips from the cupboard and throws them to us, while she starts cooking some proper meal (aerobic glycolysis). We’re eating the thrown chips in the meantime (anaerobic glycolysis). When the wife brings the proper meal, we’ll make a stash in our pocket again. And send her to make the next meal (and chips). In an hour, grandpa will return, we’ll get lard (fat metabolism), and send grandpa to the garage again. If we’re facing a TV marathon and can eat slowly, we can start sending the wife less often, grandpa’s lard will be enough. But if we need to eat very quickly. Then we’ll stop sending grandpa altogether (too much hassle), but we’ll send the wife back and forth very often. (#sorry :)

Intensity Zones. Lactate

In this whole process, we want to measure something to understand the intensity at which we’re transforming energy. One parameter we can measure is the amount of lactate in the blood.

Blood lactate concentration depends on its production and consumption. Lactate is produced not only in fast muscle cells, but also in red blood cells, in the brain, in the gastrointestinal tract. Lactate is consumed in slow muscle cells, fast muscle cells (they both produce and consume it simultaneously, just in different proportions), the liver (when needed), the heart (it especially loves lactate and feeds on it at every opportunity), as well as in the brain and adipose tissue.

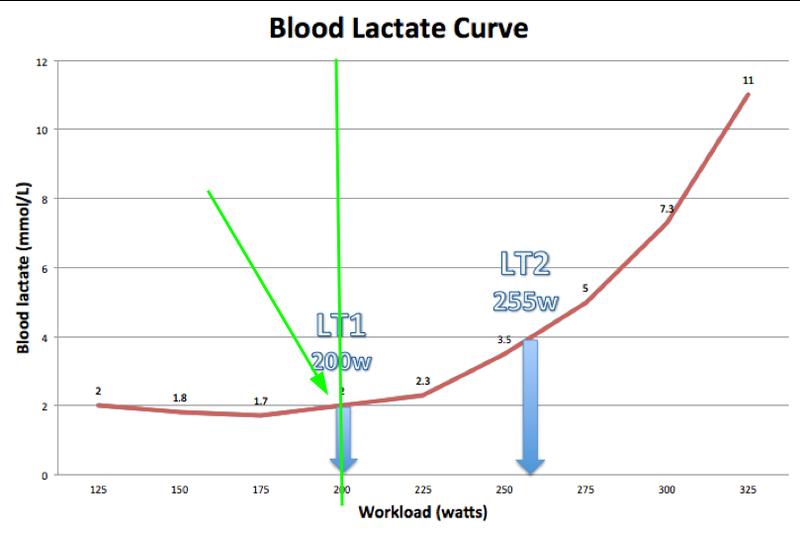

When we start moving, the amount of lactate in the blood even decreases at first, since lactate is fuel.

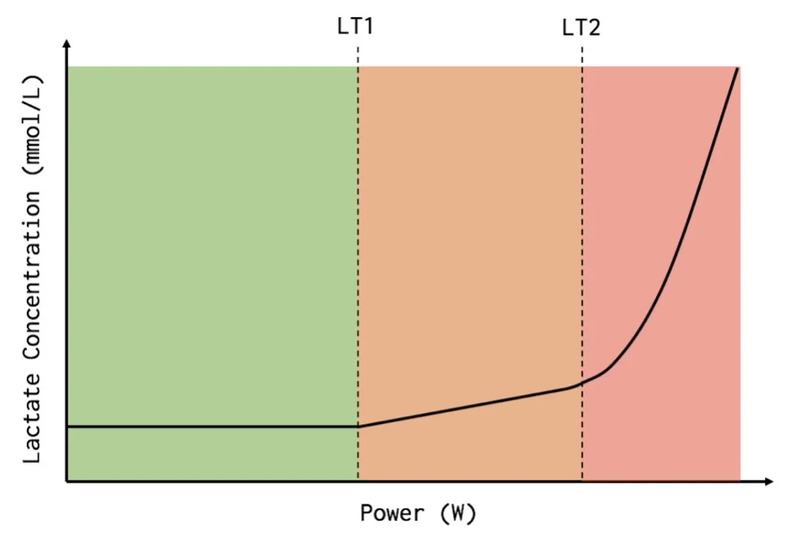

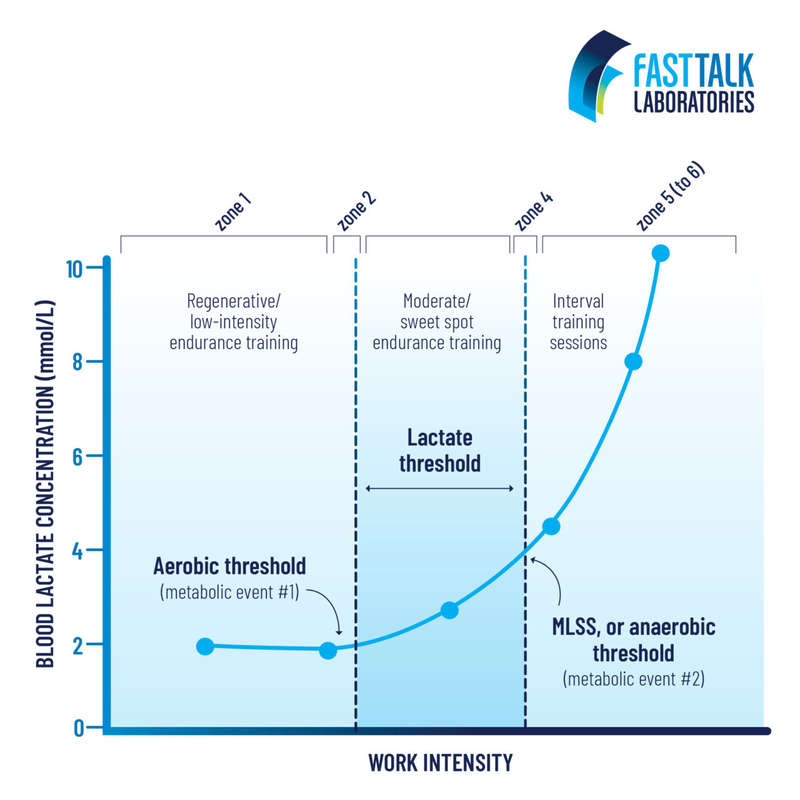

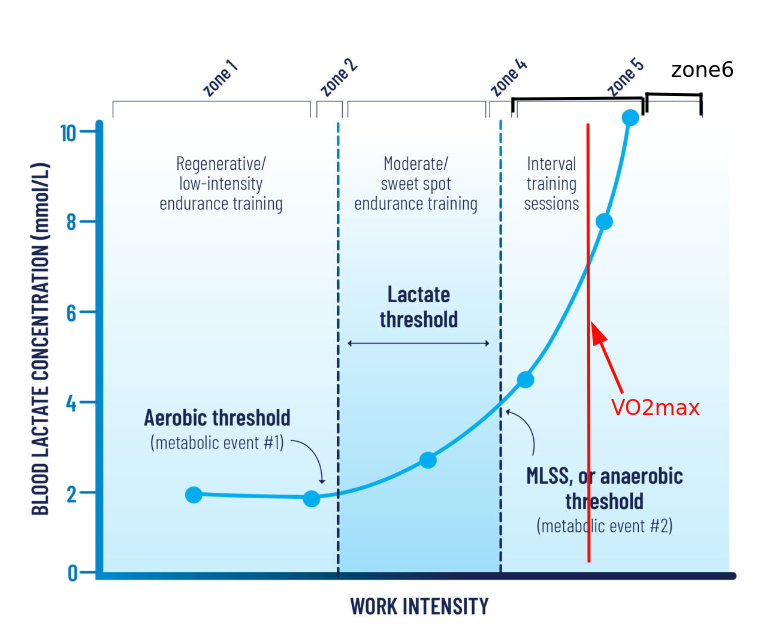

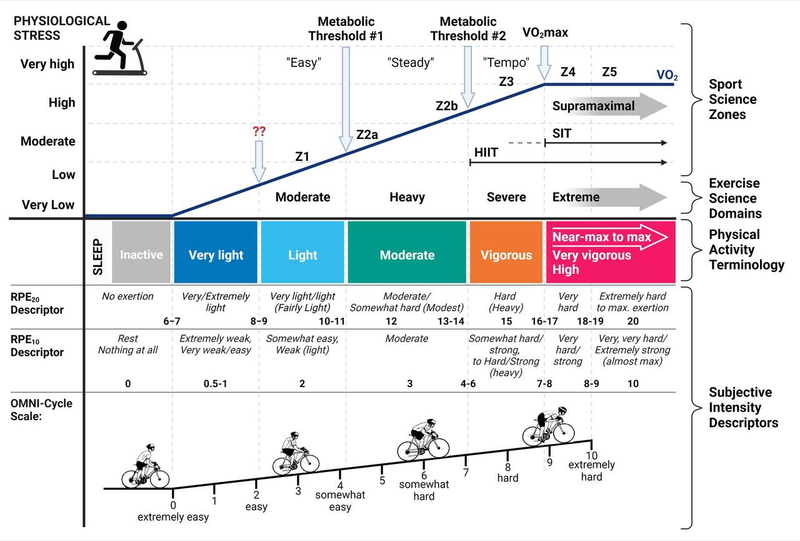

When we add intensity, the lactate level in the blood starts to increase gradually, but not much. We’re breaking down glucose, lactate exits into the blood but quickly goes back in for ATP production. Then, as the load increases, the lactate level starts to increase noticeably. This is the point of beginning blood lactate concentration growth. This point on the „lactate level/intensity” graph is called LT1 — first lactate threshold. The approximate lactate content here is 1.5–2 mmol/L. Since the utilization of pyruvate and lactate is tied to oxygen consumption, this point can also be noticed nearby on another graph, the oxygen consumption graph. And it’s called the first ventilatory threshold, VT1. In Russian, this is called the aerobic threshold.

In the three-zone model, this point is the boundary between the first and second training intensity zones.

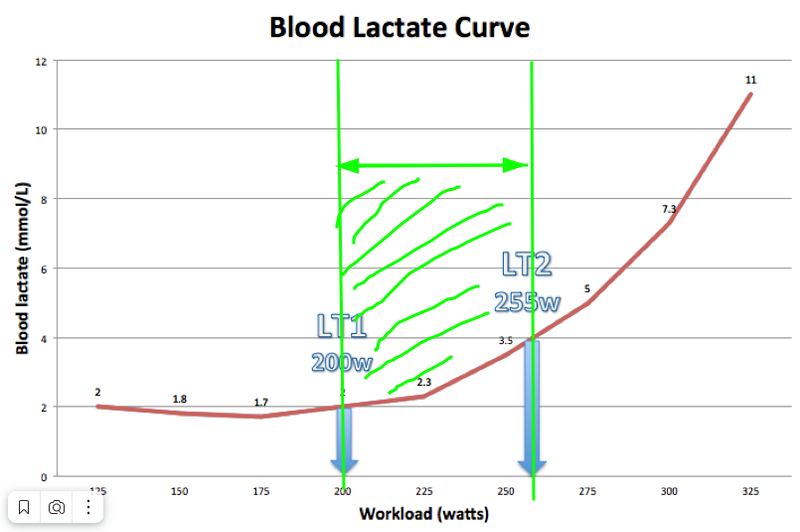

Further, we continue to increase intensity, lactate continues to grow. But the trick is that if we stop increasing intensity, then the growth of lactate level also stops. That is, at each pace here we can stay for some reasonable extended amount of time without drowning in lactate. This is called Lactate Steady State. Actually quasi steady, since nothing is constant and after some time drift will begin anyway. This is the zone that cyclists love for training, here’s their „sweet spot,” somewhere around here we run a marathon.

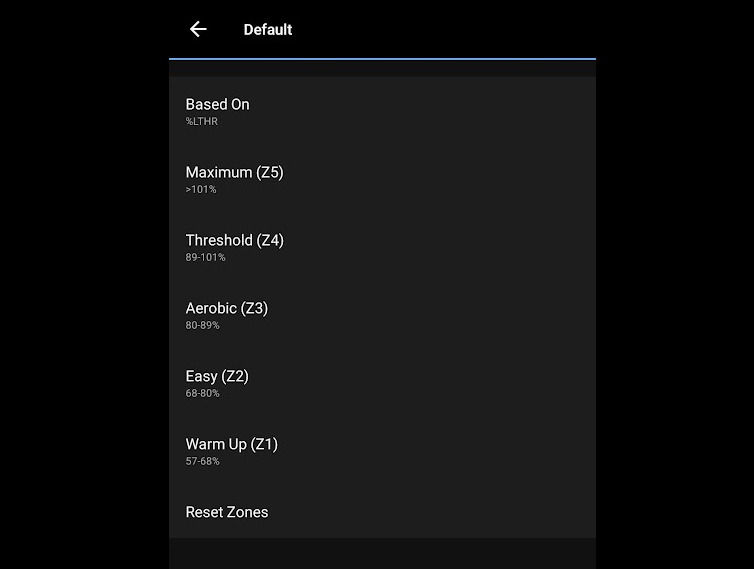

But then, at some point, if we continue to increase intensity, lactate will start to grow exponentially. And despite the fact that the pace will be constant, lactate will still grow, because we’ve already started to exceed our ability to utilize it (conditionally — there are almost no free mitochondria left). This transition point is called LT2 — second lactate threshold, MLSS — maximal lactate steady state. The approximate lactate content here is 4 mmol/L. Here will also be the second ventilatory threshold. And in Russian this is called LTHR — lactate threshold heart rate — a bastardized name, since there’s no transition to anaerobic metabolism here. We just need more energy, we just continue to break down even more glucose, getting crumbs of ATP from it, but can’t keep up with the further process — breaking down pyruvate/lactate.

Here is also where FTP — functional threshold power — is located, the intensity at which you can last for about an hour. Jack Daniels also calls this intensity the competition pace for 1 hour. What’s interesting is that actually, not many can sit here for an hour, and you could call this the pace of competitions lasting from 20 minutes to an hour. For us, this is probably the competition pace for 10–15 km.

If we take these two thresholds, we get Dr. Stephen Seiler’s zone system. He was the first to introduce the term polarized training, 80/20.

People interpreted his theory as meaning that 80% of training should occur below LT1 and 20% — above LT2. But he now claims that actually he means „intensity,” which always goes together with time at that intensity. Therefore, training between LT1 and LT2 he also counts in these 20%. Just these should be longer duration workouts. He also claims that after training below LT1 the body recovers quickly (they measured HRV), literally in an hour, and above — slowly, a day.

Having these two thresholds, you can get not only a three-part zone system, but also a five-part one. Then the second zone will be around LT1, and the fourth — around LT2.

In Garmin, for example, you can choose to have the watch calculate heart rate zones based on the second lactate threshold heart rate, then we get exactly these five zones in meaning:

Oxygen. VO2max

After we’ve stepped over our LT2 or LTHR, we still have one more point ahead that we can measure — VO2 max, maximum oxygen consumption. This means, as is clear from the name, that after crossing the LT2 we’re still increasing the use of our aerobic system, since oxygen consumption is growing, and we need oxygen precisely for the aerobic system. Which is our main system.

Thus, the VO2max indicator is the maximum indicator of our main energy system’s capacity. High VO2max reflects our high ability to produce energy.

What limits VO2max? Let’s recall our process: we need to drag food to the cell, break it down, drag the scraps to the mitochondria, drag oxygen to the mitochondria, drag this oxygen to the cell with blood through capillaries, for this fill the blood with oxygen and push it to the muscle. Each point of this process is a limiter. At each point adaptations occur.

Fuel

If we have little fat and carbohydrates, we have nothing to break down, nothing to oxidize. We’ve hit the ceiling already here.

Training increases our glycogen depot, improves the work of hormones, enzymes regulating the amount and delivery of glycogen. Top athletes train and look for other clever ways to deliver as much glucose as possible to cells during training.

Special training improves our ability to deliver and break down fats. For example, research shows that in top athletes there’s always a „droplet” of fat in the cell right next to the mitochondria, ready for use. We usually don’t have that.

It’s claimed that training in the FatMax zone (usually 50–70% of VO2max, approximately zone 2) strongly promotes the development of fat metabolism.

Mitochondria

Thanks to training, the quantity of our mitochondria and their quality increases. If we have few of them, we have nowhere to actually bring this food and oxygen.

Slow training in zone 2 particularly promotes increasing the quantity of mitochondria.

And fast training in zone 5 particularly promotes improving their quality, size.

It’s claimed that training in the FatMax zone (zone 2) is the most optimal way to develop our mitochondrial network.

Oxygen Delivery

Inside the cell, oxygen moves to the mitochondria with the help of myoglobin. Its quantity is also a limiting factor and develops with training.

Oxygen must reach the cell through a network of capillaries. The capillary network is a limiting factor and develops with training.

In blood, oxygen travels by attaching to hemoglobin in red blood cells. The greater the blood volume, the more hemoglobin in this blood, the more oxygen we can deliver. Top athletes have higher blood volume. Just by transfusing some additional blood, one can increase VO2max. And you can also inject erythropoietin, a hormone that increases the number of red blood cells → which means the ability to deliver oxygen to mitochondria will increase → which means, with other systems trained, VO2max will rise.

Blood Oxygenation

Blood oxygenation occurs in the lungs. A system that for most people is not a limiting factor. This is evidenced by such facts that a person can live and even run marathons with one lung. Also, the oxygen saturation of capillary blood, which we all measured with a pulse oximeter during COVID, is a more or less constant value, even during heavy interval work.

Note: in elite athletes at peak load, exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia (decreased blood oxygen saturation) can occur.

Heart

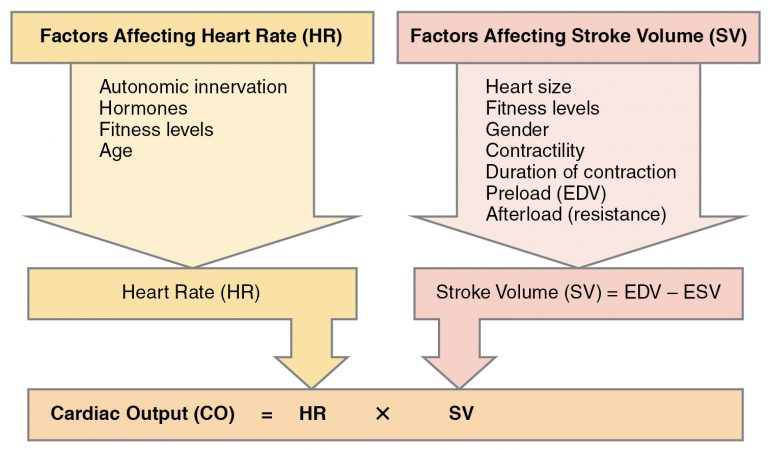

The volume of blood ejected by the heart is usually called „Cardiac Output” or (in Wikipedia) „minute volume of blood circulation”. It’s calculated as the product of Heart Rate (per minute) and Stroke Volume (amount of blood ejected per beat). In this formula, we train stroke volume. We train it by increasing heart size and by strengthening its walls.

Slow training in zone 2 particularly promotes increasing heart size.

And fast training in zone 5 particularly promotes strengthening, thickening of the heart walls.

Here’s how the process works: we have systole — the phase when the heart contracts and ejects blood, and diastole — the phase when the heart relaxes, fills with blood and feeds itself. When our HR increases, accordingly, the time for systole+diastole decreases. It decreases due to the reduction of diastole time. And this means that we collect less blood with each beat, and also that we feed the heart itself worse and worse.

When we just start running, this causes an increase in HR, it also provokes an increase in Stroke Volume. Cardiac Output and the rate of blood return to the heart increase. However, as HR increases, diastole time shortens and, consequently, we have less time to fill the heart with blood. Despite the fact that filling time is less, Stroke Volume still remains high. HR continues to increase further, Stroke Volume gradually decreases due to reduced filling time. Cardiac Output stabilizes, as the increase in HR compensates for the decrease in Stroke Volume, but at very high HR values, Cardiac Output will eventually even decrease, since further increase in HR can no longer compensate for the decrease in Stroke Volume.

Let’s add numbers for clarity.

- Here we start running, initially, when HR increases from resting state to about 120 beats per minute, Cardiac Output level will grow.

- When HR increases from 120 to 160 bpm, Cardiac Output remains stable, as the increase in frequency is compensated by the decrease in heart filling time and, consequently, Stroke Volume.

- HR continues to rise above 160 beats per minute, Cardiac Output decreases, as Stroke Volume decreases faster than HR increases.

These approximate numbers and the fact that coronary circulation feeds the heart during diastole (which means this ability decreases as HR increases), show that from the point of view of optimal heart training specifically, it’s most beneficial to train without climbing high in heart rate (for the guy in the example — this is the zone of 120–160 beats per minute).

Also, excess training at high heart rate and deficiency at low leads to a small heart with thick walls. And this is concentric cardiac remodeling (pathological if extreme).

Intensity Zones. Summary

If we take our previous picture with five zones and add VO2max to it, and count it as a separate zone, after which there’s still life, we’ll get a more standard and applicable training model:

Zone 1 — Active Recovery

RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) < 2. For some it’s walking, for some it’s jogging, for some even faster. You can chat so that your interlocutor won’t even notice you’re exercising.

Zone 2 — Base Endurance Training

RPE — 2–3. Around the first lactate threshold. Imagine you could run like this all day if needed. But you already need to concentrate a bit. You can still chat, but your interlocutor will notice you’re training now, but it won’t interfere yet. What Jack Daniels calls Easy pace. For me, this is a heart rate of 130–150.

Zone 3 — Tempo

RPE — 4–5. Some fartlek. Or you can run a long one with friends (but alone you don’t want to run this fast anymore). You’re already breathing rhythmically, working. What Jack Daniels calls Marathon pace.

Zone 4 — Threshold

RPE — 5–6. Around the second lactate threshold. Hard to talk. Mentally tough. What Jack Daniels calls Threshold pace. Long intervals with short active rest. For me, this is a heart rate of 160–167.

Zone 5 — VO2max

RPE — 7–8. Very hard to talk and think. What Jack Daniels calls Interval pace. Intervals of three to five minutes (800m — 1500m). And the same amount of rest. Main developer of maximum aerobic power.

Zone 6 — Anaerobic

RPE > 8. What Jack Daniels calls Repeats pace. Intervals of 30 seconds to 1.5 minutes (200m — 600m). Rest a lot between repeats. Develop speed, form, running economy.

Or like this:

Intensity zones

Intensity Zones. Measurement

Intensity zones can be measured in laboratories. This is cool, but needs to be done periodically because they’re constantly moving. You also need to properly choose a specialist and measurement protocol.

You can determine VO2max in the laboratory and calculate zones as percentages of it. You can determine LTHR in the laboratory and calculate zones as percentages of it. You can determine maximum heart rate and resting heart rate and calculate zones as percentages of them. But all this will be written with a pitchfork on water. Constantly moving. And the percentages themselves are different depending on the athlete’s characteristics and fitness.

You can calculate zones based on competition results. Competitions determine our maximum capabilities most accurately and adequately, if, of course, we approached them competently :) For this, we use Daniels’ (VDOT) or McMillan’s calculators.

Or you can use RPE.

Practice

Managing stress, signal, pace.